Negotiations between employers and trade unions in the private sector reached an agreement in the spring which was then put to the vote by the union leaders, recommending the agreement be accepted. But the workers, after seeing the figures for record company profits (60% increase since 1993), and also because of the increase in the pressures at work, voted against by 55%.

Some of the key demands of the strike were for an extra week’s paid holiday a year and the introduction of a 35 hour week. It was mainly a strike in which workers were demanding a share in the enormous profits they had created for Danish bosses and also an end to the increasing pressures and stress at work.

The strike affected the food industry, breweries, road transport, buses, ferries, airports, petrol stations, engineering, building industry, newspapers, etc. This in a country with a population of 5 million meant that Denmark was completely shut down for the ten days that the strike lasted.

The bosses launched a propaganda campaign saying that the strike would cause food shortages, people were going to die for lack of medicines, and there would be general chaos and mayhem. But the unions put up posters saying they will guarantee food and medicine distribution in emergency cases and the strike proceeded in a very calm and organised way.

The bosses threatened a lock out affecting the retail service to add to their propaganda.The reply of the strikers was that they would provide for any one in need, making sure that food and medicines were delivered where and when needed.

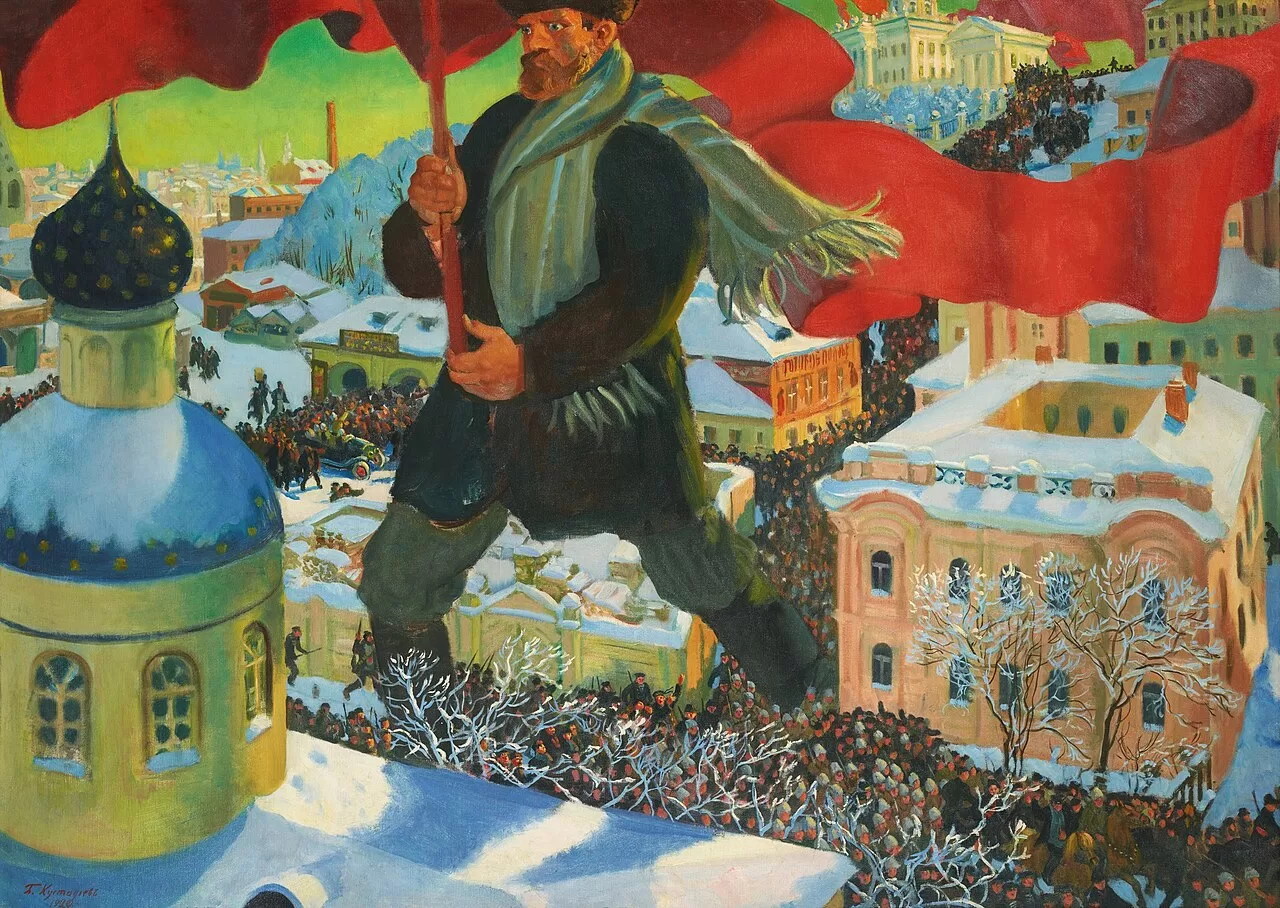

As one shop steward put it at the national shop stewards meeting: “you see, it is the employers who want to shut down Denmark, not us. They cannot run the country without the workers, but we can run the country without the employers”.

And these were not just words. For instance in order to get petrol you needed an authorisation signed by the transport and general workers union. And they only signed in cases of genuine emergency (ambulances, etc.), without that, not even the police could get petrol. Every general strike poses the question: “who runs society,” and the answer was quite clear in the minds of Danish trade unionists.

The strike started in the private sector, because the bosses split the negotiation rounds for public and private sector workers a while ago in an attempt to divide the workers in order not to have to face them all at once. Nevertheless, because the cleaning services in the public sector have been privatised, the strike also affected the public sector. Workers there joined in, using health and safety grounds (rubbish was not collected) to do so.

Supported demands

Workers in the public sector also supported the demands, and an extension of the strike to the public sector was always a possibility. This would have guaranteed the victory of the movement.

On April 29th, there was a national shop stewards meeting of 1200 in Odense. The meeting agreed the formation of national and local coordinating committees to organise the running of the strike. This was the result of a widespread feeling that the trade union leaders were too busy in negotiations with the bosses to offer any meaningful lead to the strike.

Nevertheless not even the leadership of this shop stewards movement was able to offer a way forward for the strike (i.e. its extension to the public sector).

The May Day rally in Copenhagen was a massive event which marked day 5 of the all-out strike. Between 350,000 and 500,000 workers participated in the rally.

The strike received important international support despite the deafening silence of the international media about the movement. Airport workers in Sweden refused to handle flights to and from Denmark. The Finnish trade unions also declared that they were not prepared to take on any job transferred from Denmark.

Support for the movement and opposition to government intervention to stop it, was growing throughout the strike with an opinion poll published on May Day showing more than 50% support for the strike (including 2/3rds of Social Democratic voters).

The strike remained solid all the way and the employers started to complain about a “workers’ dictatorship” as they had to ask permission from the unions for any movements they wanted to make.

Many foreign investors and foreign companies dealing with Danish firms said that if the strike went on for more than 10 days, they were going to withdraw all their operations. This could have had a long term effect for the Danish economy. Therefore the government (a Social Democratic led coalition), on day 11 of the strike decided to pass (with the votes of the bourgeois parties and the Social Democracy) a law of compulsory arbitration based on the original offer already voted down by the workers.

The mediators’ proposal voted down by the workers two weeks ago added one extra day off to the Danish workers’ existing five weeks annual holiday entitlement. The new law also gave one extra day off for all workers who have at least nine months’ service with their current employer, plus two more days off for workers who have children under 14 years of age (and a further day off for workers in this category from 1999 onwards).

To finance these additional holiday entitlements, the increases in pensions contributions that were to have been paid by employers would be reduced by 0.4 per cent of the wages bill. The government would also cancel the special sick leave levy under which the employers have to pay 325 Danish kroner per employee to the state.

In effect the cost of the extra days holidays is being paid by the workers themselves and by the government and was described by one of the strikers as “feeding the dog with his own tail”, insisting the bosses had had enough profits to afford to pay for an extra week holidays without compensation. Another striker said “all the young people we have recruited during the strike would leave the union immediately if we just give them this agreement”.

Lack of leadership

The problem is that the strike effectively had no leadership. The trade union leaders were busy negotiating and offered no way forward. The shop stewards movement which was actually organising the strike had no clear strategy either. In these conditions it is difficult to see how the anger with the government implementing a forced deal could be expressed.

An important meeting of shop stewards took place on May 7th, the same day that Parliament was discussing the arbitration law. It had been planned as a national shop stewards meeting, but it was finally reduced to a Zealand region (where Copenhagen is) shop stewards meeting to discuss the outcome of the strike.

The leader of the national trade unions went to this meeting hoping to convince the shop stewards that this was the best agreement they were going to get and therefore should be accepted.

But the mood amongst the more than 1000 shop stewards present was, as it had been since the beginning of the strike, that the strike was mainly for an extra week holidays, and that anything short of that was not acceptable. Therefore, when a young apprentice stood up in the meeting and said that the national coordinating committee of shop stewards had the responsibility to take the effective leadership of the movement, maintain the strike and fight against government intervention with a general strike, the whole meeting erupted and started to shout “general strike, general strike”.

After witnessing this scene the leader of the trade union confederation quietly left the hall and didn’t address the meeting as originally planned.

The proposal was raised of calling for a national protest demo against the intervention of the government, and also the need to answer the government intervention with an extension of the strike to the public sector. These proposals were greeted with enthusiasm but the chair managed not to put them to the vote. After the meeting some 20,000 workers demonstrated outside parliament.

Left with no clear lead of what to do next most workers went back to work on Monday 11th (the first working day after the government’s intervention, as Friday was a holiday). Nevertheless, despite the fact that the strike had been made illegal by the government’s decision, on Monday in many workplaces meetings were held and the decision was taken to go back home as a protest. This was the case in the massive building site of the bridge between Denmark and Sweden, at the shipyards in Odense and many other workplaces all over the country. The protest movement was especially strong in Aalborld, the fourth biggest city in Denmark and a strongly industrialised area, where there was a demonstration with about 2000 workers. A small demonstration also took place in Copenhagen.

Financial support

Other groups of workers decided to stop their financial support for the Social Democratic party as a form of protest, as was the case with the Copenhagen airport workers. In general there is a strong feeling of anger against the government for its intervention. This will undoubtedly be reflected in the forthcoming referendum on the Amsterdam Treaty on May 28th. It will also have an effect on the negotiating round for local wage deals which could prove very bitter. Frustration on the part of the workers is particularly strong because of the feeling that, had the strike lasted for another week, they could easily have won.

This strike was remarkable from many points of view: the determination and unity of the movement, its breadth, the fact that it was an offensive movement, how scared the bosses were, etc. But maybe there are two key lessons to be learnt from it: one is that once the workers start to move their power is enormous and can bring a whole country to a standstill, secondly, and even more important, that without a clear leadership with confidence in the workers and a clear strategy for extending the struggle they cannot win. The need to build a militant opposition movement in the trade unions and the workers parties based on socialist polices is the main lesson for activists, not only in Denmark but all over Europe.